「前人种树,后人乘凉」"The predecessors plant trees and the descendants enjoy the shade." – Chinese proverb

在我生命的前 37 年,我一直满怀信心地相信,我的家人和许多加拿大华人一样,是 1970 年代从香港和其他地区移民到加拿大的。但去年,在疫情期间和反亚裔情绪高涨的背景下,我开始深入挖掘我家人的过去,发现这并不是我们第一次在加拿大定居。我们的故事始于 100 多年前,当时正值华人人头税和《排华法案》的时代,政府决心阻止长得像我这样的人成为这个国家的公民。

For the first 37 years of my life, I'd lived confidently believing that my family, like many Chinese Canadians, had begun our lives in Canada as part of a wave of immigration from Hong Kong and beyond during the 1970s. And then last year, in the middle of the pandemic and amid a surge of anti-Asian sentiment, I started to dig deeper into my family's past and discovered that it wasn't our first time as settlers in Canada. Our story began more than 100 years ago, in the era of the Chinese Head Tax and The Chinese Exclusion Act, when the government was determined to prevent people who looked like me from becoming citizens of this country.

我的曾祖父母和他们的两个孩子合影,摄于 1930 年代的中国台山。最右边的孩子后来成为我的外祖母。她花了 30 多年时间才与在加拿大的父亲团聚。 (图片由 Winston Ma 提供)

作为一个在北士嘉堡长大的华裔年轻人(粤语俚语,指在西方出生和/或长大、认同西方文化多于中国文化的华人),我更关心的是抹去我华人身份的所有痕迹,而不是了解我的家庭来自哪里。你可以想象为什么。你知道,我从未在北美媒体、电视或电影中看到过自己。从来没有任何由我这样的人创作或讲述的故事。当时对亚洲人的描述充斥着刻板的比喻:在大卫·卡拉丁主演的《功夫》等电视剧中,我们是面色黄皮肤的演员,我们是虚弱无性的背景群众演员,或我们是邪恶、阴险的“傅满洲”角色。我对自己是华人感到非常羞耻,以至于 13 岁时,我更容易接受自己的同性恋身份,而不是我的种族背景。

As a young jook-sing — a Cantonese slang phrase for a Western-born and/or raised Chinese person who identifies more with Western than Chinese culture — in north Scarborough, I was more concerned about erasing all traces of my Chinese identity than learning about where my family came from. And you can imagine why. You see, I never saw myself in North American media, TV or film. There were never any stories that were by and about people like me. The only portrayals of Asians at the time were pumped full of stereotypical tropes: yellow-facing in shows such as Kung Fu starring David Carradine, we were background extras that were weak and sex-less, and/or we were the evil, conniving "Fu Manchu" character. I became so ashamed of being Chinese that it was easier for me to come to terms with my queer identity at 13 years old than my ethnic background.

上学时,历史课上很少讲到华裔加拿大人(更不用说原住民和其他非欧洲社区的故事了)。如果提到我们,那也只是一段很小的、需要用放大镜才能找到的关于华人人头税或华人在铁路上工作的内容。从教育系统到流行文化,华裔加拿大人的故事毫无价值;难怪我那易受影响的幼小心灵认为这意味着我和我的家人不重要,不属于这里。

Back in school, little was taught about Chinese Canadians (let alone stories from Indigenous peoples and other non-European communities) in history class. If we were mentioned, it was one tiny, you-had-to-find-it-using-a-magnifying-glass, paragraph about the Chinese Head Tax or Chinese working on the railway. From the education system to pop culture, zero value was placed on the stories of Chinese Canadians; it's no wonder my impressionable young mind thought this meant that my family and I didn't matter, and didn't belong here.

但我的世界在过去几年发生了变化:我成为了一个重生的亚洲人。和许多亚裔加拿大人一样,我也在努力应对疫情期间抬头的反亚裔种族主义。在此过程中,我开始重新找回我一生都回避的中国传统。

But my world changed last few years: I became a born-again Asian. Like so many of my fellow Asian Canadians, I was grappling with the anti-Asian racism that reared its ugly head during the pandemic. In doing so, I began to reclaim the Chinese heritage that I had shunned my whole life.

(左)我的曾祖父母 Lee Chuen Oy 和 May Lee 于 1967 年抱着他们的孙子 David Lee 站在他们位于苏圣玛丽的餐馆“Oy's Restaurant/Lunch”门前 | (右)我叔叔 Donald Lee 在多伦多 Tom's Restaurant 门前的照片,他和妻子从 1960 年代起就经营这家餐馆 (Winston Ma 提供)

去年夏天,我的外祖父去世,我得知他在 20 世纪 80 年代曾在多伦多的 Bay 街和 Dundas 街开过一家中餐馆。为了了解更多,我如饥似渴地阅读了畅销书《杂碎国度》(Ann Hui 著)和《你吃了吗?》(Have You Eaten Yet?)。这两本书都以加拿大及其他国家随处可见的中餐馆(比如我祖父的餐馆)为背景,绘制了一幅加拿大(《杂碎国度》)和世界其他地方(《你吃了吗?》)华人移民的鲜活地图。

When my maternal grandfather passed away last summer, I learned that he had owned a Chinese restaurant at Bay and Dundas Streets in Toronto during the 1980s. Hungry to learn more, I devoured the best-selling books Chop Suey Nation by Ann Hui and Have You Eaten Yet? by Cheuk Kwan. Both books use the ubiquitous Chinese restaurant — like my grandfather's — found across Canada and beyond, to chart a living atlas of the Chinese diaspora in Canada (Chop Suey Nation) and elsewhere in the world (Have You Eaten Yet?).

当我在家人的圣诞晚餐上大谈这些书时,我妈妈惊喜地发现我对我们民族的故事感兴趣,于是又说了她自己的一个故事:“你知道你的曾祖父来到加拿大时缴纳了华人人头税,对吧?”听到这句话,我和我的兄弟姐妹差点被食物噎住。“等等!你是什么意思?”妈妈又给了我一个听起来没什么大不了的回答:“我以为我以前告诉过你?他在 20 世纪初来到这里,缴纳了人头税,最终定居在苏圣玛丽,经营我们家的餐馆。”

When I raved about these books during my family's Christmas dinner, my mom, pleasantly surprised that I'd taken an interest in our people's stories, added one of her own: "You know your great-grandfather paid the Chinese Head Tax when he came to Canada, right?" My siblings and I almost choked on our food when we heard this. "Waaiiit! What do you mean?" With another no-big-deal-sounding answer, my mom declared, "I thought I told you before? He came here in the early 1900s, paid the Head Tax and eventually settled in Sault Ste. Marie to run our family's restaurant."

接下来的一周,我拼命地从我妈妈和范妮姨妈(她的妹妹)那里收集尽可能多的关于我祖先的信息。我有很多问题,但答案却很少。

The following week was a game of catch-up with me desperately trying to glean as much information about my ancestor as possible from my mom and my aunt Fanny, her younger sister. I had so many questions, but so few answers.

经过一个半星期的数字化搜索,我偶然发现了不列颠哥伦比亚大学历史系的 Peter Ward 教授和 Henry Yu 教授的宝贵研究成果。他们将 1886 年至 1949 年间加拿大华人移民登记册上所有缴纳华人人头税的个人记录数字化,并将它们汇编到一张 Excel 表中。我利用我所掌握的有关曾祖父的所有细节,仔细筛选了 97,123 个列出的名字。然后,在第 85,772 行,一个听起来很熟悉的名字出现了。在仔细检查了详细信息(他的家乡、身高、列出的职业和最终目的地)后,我找到了他。

After a week and a half of going down the digital rabbit hole, I stumbled upon the invaluable research by Professors Peter Ward and Henry Yu of the Department of History at UBC. They digitized records of all recorded individuals listed in the Register of Chinese Immigrants to Canada who paid the Chinese Head Tax from 1886-1949 and compiled them in one Excel sheet. I sifted through 97,123 listed names using whatever scant detail I had about my great-grandfather. And then on line 85,772, a name popped up that sounded familiar. After triple-checking the details — his home village, his height, his listed occupation and his intended final destination — I found him.

我曾祖父的 CI5 华人人头税证明,表明他在 1918 年仅入境就支付了 500 美元。加拿大政府只向华人移民颁发这些证明。 (Winston Ma 提供)

通过这些记录和与家人的对话——包括我叔叔唐纳德,他唯一幸存的孩子——我想向你们介绍我的曾祖父李全奥(移民官员记录的)。他来到加拿大,来到“金山”(粤语,指北美的常用昵称),以逃避中国南部台山地区的贫困、战争和饥荒。1918 年 1 月 23 日,他从不列颠哥伦比亚省维多利亚的日本皇后号上下来。1918 年中国移民总登记册记录他 15 岁,是一名学生,身高 4 英尺 5 英寸。

Through these records and conversations with my family — including my Uncle Donald, his only surviving child — I'd like to introduce you to my great-grandfather, Lee Chuen Oy (as it was transcribed by the immigration official). He came to Canada, to "Gold Mountain" (in Cantonese, a commonly-used nickname referring to North America) to escape poverty, war and famine in the Taishan region of southern China. On January 23, 1918, he disembarked from the SS Empress of Japan in Victoria, B.C. He was recorded in the General Register of Chinese Immigration of 1918 as being 15 years old, a student and four feet, five inches in height.

(右) - 我的曾曾祖父李万斯 (Lee Wan Sze) 的肖像照,他是本世纪初家族中第一个抵达加拿大的人 | (左)我的曾祖父李传奥 (Lee Chuen Oy) 成年后的样子。 (由 Winston Ma 提供)

抵达后,他被迫缴纳 500 美元的华人人头税才能入境。然后他一路前往安大略省伦敦市与他的父亲李万斯见面。是的,我很惊讶地发现,我的曾曾祖父实际上是我们家族中第一个抵达加拿大的人(大约在世纪之交),但他在儿子抵达几年后就回到了中国,从此再也没有回来。

On arrival, he was forced to pay the $500 Chinese Head Tax to enter the country. He then travelled all the way to London, Ontario to meet his father, Lee Wan Sze. Yes, I was surprised to discover that my great-great-grandfather was, in fact, the first in our family to arrive in Canada (at some point around the turn of the century) but he went back to China a few years after his son arrived, and never returned.

与此同时,Lee Chuen Oy 在安大略省南部开始了一家洗衣店,但在苏圣玛丽开办自己的餐馆的机会让他向北走去。在接下来的几十年里,他在位于惠灵顿街西 92 号的 Oy's Restaurant/Lunch 餐厅辛勤工作。他渴望带着家人来到这片土地上,开始共同生活,但 1923 年《华人移民法》(通常称为《排华法案》)的出台让他的梦想破灭了,该法案禁止几乎所有华人移民入境。这是第一部也是唯一一部禁止种族入境的移民法,它将阻止像我曾祖父这样的人、其他入籍的华人移民和在加拿大出生和长大的华人带着他们的家人过来,直到 1947 年法律被废除。为了结婚生子,他必须有限度地返回中国,并在两年内返回加拿大,否则将失去他的身份。

Lee Chuen Oy, meanwhile, started a laundry business in southern Ontario, but an opportunity to run his own restaurant in Sault Ste. Marie led him north. For the next few decades, he toiled away at Oy's Restaurant/Lunch, located at 92 Wellington Street West. He was eager to bring his family to this land and begin a life together, but those dreams were stolen from him in 1923 with the introduction of The Chinese Immigration Act (commonly called the Chinese Exclusion Act), which banned the entry of virtually all Chinese immigrants. It was the first and only immigration law that banned entry by race, and it would keep people like my great-grandfather, other naturalized Chinese immigrants and born-and-raised-in-Canada Chinese from bringing over their families until the law was repealed in 1947. In order to marry and start a family, he would have been able to take limited trips back to China, and return to Canada within two years or lose his status.

当时,白人,特别是英联邦国家的白人,获得了巨额的经济奖励,成为加拿大的定居者。根据1922 年的《帝国定居法案》,加拿大政府与英国政府达成协议,为本国公民在加拿大工作提供补贴,并确保“英国价值观”占主导地位。这些英国移民甚至被鼓励带朋友和熟人过来,而像我的曾祖父这样付出高昂代价才进入加拿大的人,却被迫成为“已婚单身汉”,甚至连最亲近的家庭成员都不能带过来。

During this time, white people, specifically from Commonwealth nations, were given huge financial incentives to become settlers in Canada. With The Empire Settlement Act of 1922, the Canadian government entered into an agreement with the British government to subsidize their citizens to work in Canada and to ensure "British values" dominated. These British immigrants were even encouraged to bring over friends and acquaintances, while people like my great-grandfather, who had paid dearly to enter Canada, were forced to become "married bachelors," unable to bring over even their most immediate family members.

1954 年,我叔叔唐纳德·李 (中间那个身着西装、手拿行李袋的孩子) 在香港启德机场拍摄的照片,当时他正准备前往加拿大与父亲李全爱第一次见面。 (Winston Ma 提供)

20 世纪 50 年代初,我的曾祖父终于获准带他的一些家人来加拿大。他的妻子 May Lee 和两个孩子是第一批抵达加拿大的人,其中包括当时还未成年的 Donald 叔叔。他的其他家人,包括我的母亲和亲戚,直到 20 世纪 70 年代才获准入境。他们只在一起生活了一两年,最终作为一个大家庭生活在一起,我的曾祖父和他的妻子分别于 1973 年和 1974 年去世。

In the early 1950s, my great-grandfather was finally allowed to bring over some of his family. His wife, May Lee, and two of his children were the first to arrive in Canada, which included my Uncle Donald who was just a pre-teen at the time. The rest of his family, which included my mom and relatives, weren't allowed in until the 1970s. They only had about a year or two to finally live together as one big family before my great-grandfather and his wife passed away in 1973 and 1974 respectively.

20 世纪 70 年代初,李传奥抵达加拿大 50 多年后,我们一家终于团聚了。1967 年,基于种族和国籍的移民限制终于被完全取消。这是我曾祖父 1973 年去世前的最后一张照片之一。

对于许多亚裔加拿大人来说,疫情迫使我们面对一些令人不安的事实。从被指责给世界带来了“功夫流感”,被问到“你来自哪里?不,你到底来自哪里?”,到看到我们的长辈遭到暴力袭击,其他人被杀害,很明显,无论我们与加拿大社会的融合程度如何,我们首先被视为亚洲人——外国人,从未完全属于或忠诚于这个国家。我不得不承认这种异化,并最终开始解开我从童年起就内化的种族主义。

For many Asian Canadians, the pandemic forced us to confront some uncomfortable truths. From being blamed for giving the world "Kung flu", asked, "Where are you from? No, where are you really from?" our entire lives, to seeing our elders violently attacked and others killed, it's become clear that no matter how integrated we are in Canadian society, we are first viewed as Asian — foreign, never quite fully belonging or loyal to this country. I've had to acknowledge this othering and finally start to unpack the racism I'd internalized since childhood.

今年是华人移民法通过 100 周年 ,我开始为自己的出身感到自豪。在拼凑起我自己的家人来到加拿大的旅程后,我能够更好地描绘出我的祖籍,这样我就可以纪念我的祖先和他们的牺牲。

With this year marking 100 years since the Chinese Immigration Act was passed, I have begun to take pride in my background. Having pieced together my own family's journey to Canada, I am able to paint a better picture of where I descended from so I can honour my ancestors and their sacrifices.

我的祖先——就像我的曾祖父李传豪一样——勇敢而坚强。他们面对着不友好的环境,坚持不懈。他们在逆境中坚韧不拔,从未抱怨过种族主义社会和政府在他们努力建立生活、事业和家庭时夺走了他们的梦想。

My ancestors — like my great-grandfather Lee Chuen Oy — were brave and strong. They faced an unwelcoming environment and they persevered. They were resilient in the face of adversity, never once complaining about the racist society and government that stole their dreams when they were trying to build lives, businesses and families.

(Winston Ma(右二)供图)

成千上万的加拿大华人为了下一代能够登上“金山”之巅而移山倒海。我现在知道我的力量和决心来自哪里。我花了 37 年的时间,但现在我终于可以说,我从未像现在这样为自己是加拿大华人而感到自豪

Hundreds of thousands of Chinese Canadians moved mountains so the next generations could climb to the summit of "Gold Mountain." I now know where my strength and determination come from. It took me 37 years but I can now finally say that I have never been more proud to be Chinese Canadian

文章来源:Winston Ma (馬英賢)

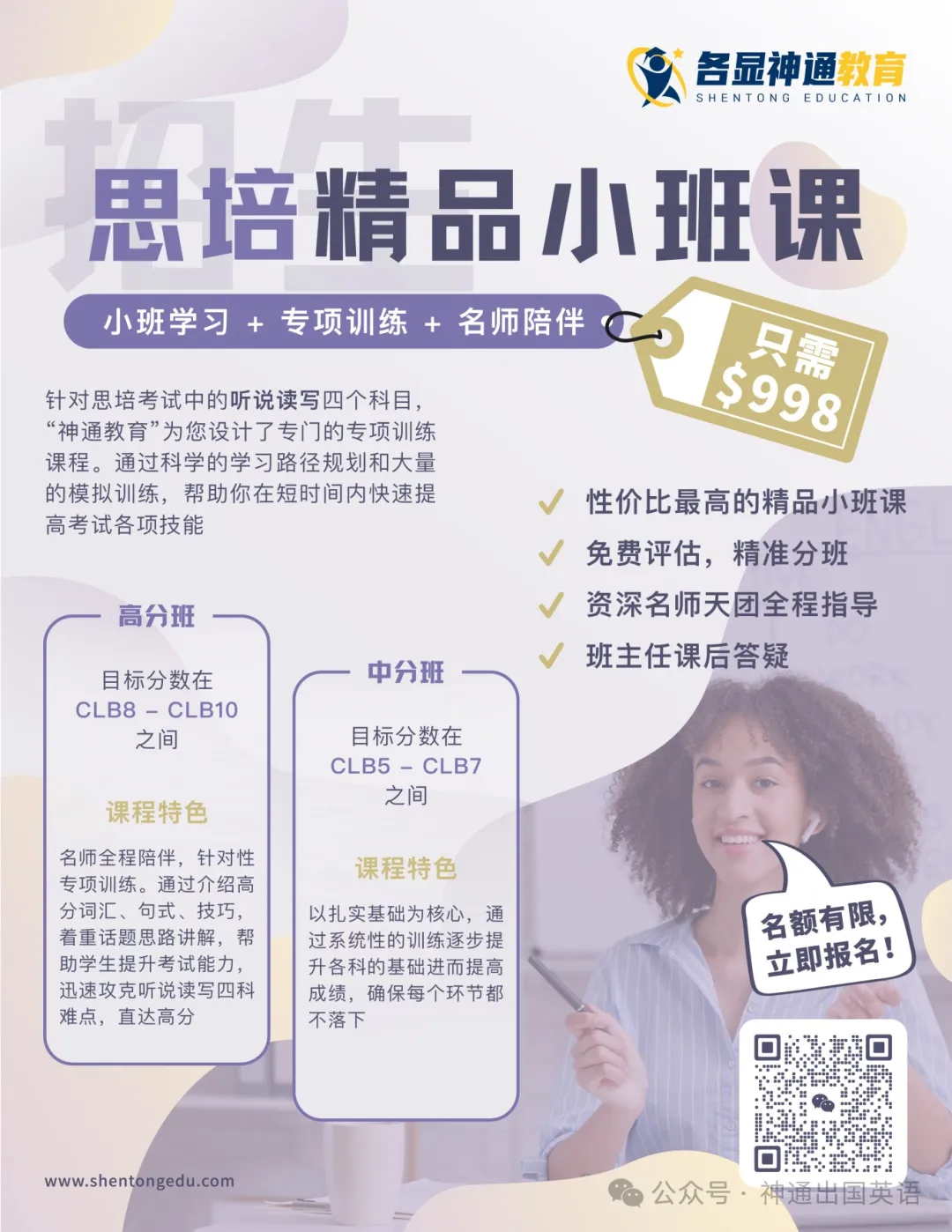

重磅!神通推出思培精品小班课!

如果大家有任何与加拿大思培考试和雅思G类考试的相关问题,欢迎与神通教育(神通出国英语)联系!在这里,有资深老师带大家学习,灵活的时间、定制的课程、真正的雅思G类、思培保分,为大家的移民类英语考试之路保驾护航!